Spring 2016

The Trouble With Bats

A decade after the emergence of white-nose syndrome, bats in national parks and around the country continue to die. Can researchers save them before it’s too late?

We’re driving along the northern curve of Acadia’s Park Loop Road, a mile from the Maine coast, under a canopy of maples and aspens just past peak color—riotous reds and yellows—when the pinging begins. First a faint bleep, bleep. Then louder.

“There,” says Bruce Connery, the park’s wildlife biologist. “You hear it?”

The antenna mounted on the van’s roof has picked up a signal. We’re close. Connery pulls over and a staff member, Chris Heilakka, gets out with a handheld, three-wand antenna and points it toward the hillside, swiveling his wrist. More bleeps. We start up the grade, stumbling over birch logs and lichen-slick stones to reach a bedrock outcropping, a cluster of granite boulders formed by the pressure of ancient glaciers.

A researcher at Acadia checks an eastern small-footed bat for signs of damage caused by WNS.

© CHRIS HEILAKKAIt’s late October, the end of mating season for bats. We’re tracking a female eastern small-footed bat, one of the Myotis (“mouse-eared”) species hit hardest by white-nose syndrome, or WNS, the devastating fungal disease that’s killed an estimated 6 million bats in the United States and Canada over the last decade. Two weeks earlier, this bat flew into a giant net, big enough to stretch between football goalposts. It was erected by a team from the Biodiversity Research Institute, a Portland-based ecological nonprofit that’s been working with Acadia National Park staff to study bats since 2009. After affixing a pea-sized transmitter to her body, the team released the bat, as they’ve done with around 100 others. By following them, the researchers are learning about how bats use the park: where they roost, spend winters, and raise their pups. Such work is now part of a nationwide effort to survey bats, which, in affected areas, are still dying. Conservationists hope the collected data will create a fuller picture of the disease’s impact and pathology, leading scientists toward ways of slowing its spread, or even a cure.

Heilakka aims at a fissure; the bleeps intensify. Bingo. Nestled deep in the rocks, our bat is asleep, the transmitter’s four-inch antenna curled around her like a tiny steel tail. I ask about extracting her. Connery shakes his head. It’s so late in the season, she could be hibernating. And for millions of bats afflicted with white-nose syndrome since its appearance in North America in 2006, waking from hibernation has meant death.

Connery knows this firsthand. He remembers occasionally finding dehydrated, starved bats strewn on the snow, after the disease swept into Maine six years ago. In winter of 2011, he started getting reports of bats crawling around outside or day flying, and by the following winter mortality rates in the park had clearly spiked. “I found dying or dead bats in a few dozen areas of the park and on adjacent lands,” he said. Summer mist-net catches had plummeted, too, and many of the captured bats had scars on their wings from the fungus, a white fuzz that invades soft tissues.

By then, scientists had figured out that the cold-loving fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, targets bats during hibernation, when their immune systems are repressed. Body temperatures of wintering bats can drop to as low as 53 degrees Fahrenheit, and since they often huddle in large groups, the disease can spread quickly, wiping out entire colonies. But the fungus, though deadly, doesn’t kill bats directly. Rather, it stresses them and speeds their metabolism, so they awaken and burn precious fat reserves. Desperate for energy, the bats leave hibernacula to forage outside, where, facing harsh conditions and meager food sources, many die of starvation or exhaustion.

Scientists think the fungus arrived in the United States from Europe, after crossing the Atlantic on the clothing and gear of spelunkers or other recreational cavers. (European bats are genetically resistant to white-nose syndrome, having likely coevolved with the fungus over centuries.) Since the disease’s discovery in upstate New York, its spread has been constant but erratic, making it tough to predict and study. “In 2009 and 2010, white-nose started spreading in places nobody expected,” Connery explained. “It was moving 300 miles in a jump, and it was like, how did that happen?”

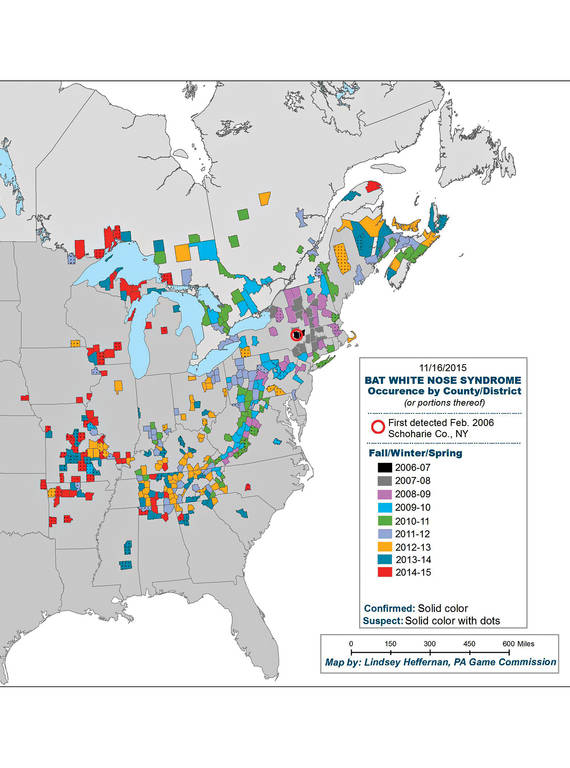

Now confirmed in 30 states and 11 national parks, the fungus has been detected as far as Nebraska.

Lindsey Heffernan, PA Game CommissionColor-coded maps from the Pennsylvania Game Commission bear this out: from its origin point near Albany, white-nose syndrome blooms in all directions, sometimes leaping over half a state or across a great lake in a single year. Rogue outbreaks appear like errant pixels. Now confirmed in 30 states and 11 national parks, the fungus has been detected as far as Nebraska, and its westward sprawl shows no signs of stopping.

Across New England, the toll has been huge. Once robust populations of little brown bats have fallen by as much as 90 percent, and the northern long-eared bat is now federally listed as threatened. In response, conservation groups have petitioned for these species, along with the already rare eastern small-footed bat, to be given endangered status. The future of these aerial hunters can look even grimmer in light of additional threats including pollutants, habitat loss driven by construction and gas drilling, and wind turbines, which are particularly deadly to migratory bats.

“In Maine right now it’s not good,” said David Yates, mammal program director at Biodiversity Research Institute and a lead researcher on the Acadia team. “I spent 11 nights mist-netting in Maine, and I caught five bats the whole time. Pre-white-nose, I would usually catch 20 to 50 bats a night. It’s awful.”

In other parts of the country, especially regions with caves, tunnels, or abandoned mines, dead bats around a single large hibernaculum can number in the thousands. The WNS crisis has prompted a cooperative effort by ecology groups, university-backed researchers, and government agencies to better understand the fungus and take measures to curb its spread and potential transmission by humans. At Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area and Great Smoky Mountains National Park, for example, all caves have been closed to the public since 2009. In Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, stricter decontamination procedures are in place for visitors and cavers, serving as a model for other bat havens like Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, where the fungus has yet to strike. In many forests, new regulations ban commercial cutting in areas where maternity colonies (groups of female bats raising pups communally) are thought to exist. “The Park Service is taking a multi-pronged approach to manage WNS,” said Margaret Wild, the agency’s chief veterinarian. “Individual parks are monitoring bats, educating visitors on the importance of bats and how they can prevent the spread of the disease, and putting up gates to protect bats in mines or caves.” This year the National Park Service committed $3 million to WNS-related projects, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has pledged $2.5 million.

In Acadia, such grants have been critical, allowing for more mist-netting hours and the purchase of acoustic monitors to capture high-frequency bat calls, which are recorded nightly and fed through software that can identify species by their unique sounds. This equipment, used also to record songs of birds and whales, has vastly improved the staff’s understanding of feeding hotspots and population dips in the park.

Although the recent funding is encouraging, even millions can quickly disappear in the midst of an epidemic (the Park Service alone has 43 ongoing bat projects, across 40 parks). Many bat advocates think that the government’s reaction to the WNS crisis has been too measured, and far too slow.

“Abundant, non-game species? There’s no money for that,” Yates said. He thinks the sluggish national response is the result of a public relations problem: Bats are widely feared and misunderstood. They seize our imaginations in haunted houses, comic books, and films, but they don’t exactly tug people’s heartstrings. “It’s not a polar bear,” he said. “It’s not a charismatic animal that brings that emotion.”

The irony is that bats may do more for ecosystems and economies than photogenic, high-profile predators like cheetahs and polar bears ever could. Along with pollinating plants and dispersing seeds, bats consume hundreds of tons of insects. According to a 2011 study published in the journal Science, the natural pest-control bats provide saves the U.S. agricultural industry up to $53 billion each year. “Since they eat thousands of insects every night, if you take that out of the picture, then suddenly something’s changing,” Connery said. “You may not sense it right away, but there’s got to be a ripple effect there.” As bat numbers dwindle, farmers may be forced to use more pesticides, upping our intake of these chemicals. Spruce budworm, an insect scourge of northeastern forests eaten largely by bats, could decimate Maine’s timber industry. Fewer bats could also result in less obvious environmental effects such as a higher prevalence of disease-carrying mosquitoes or the loss of rare cave-dwelling organisms that depend on nutrients in bat guano.

So far, the Acadia team has not detected major ecological shifts due to bat losses; the park’s natural systems appear stable. But its research has yielded other discoveries. Most surprising is that many of the park’s bats, previously thought to migrate inland during the winter, probably don’t. Acadia includes 47,000 acres of protected marshland, spruce-fir and hardwood forests, glacially sculpted mountains, cobble beaches, and 45 miles of broken-stone carriage roads. But the park lacks one feature scientists assumed was essential for hibernating bats: caves. In recent years, the Biodiversity Research Institute team has used airplanes equipped with receivers to locate marked bats from the air. At first, the plan was to pursue the bats to their distant winter hideaways. Instead, they found themselves circling Mount Desert Island. “We were going to follow them on their migration path,” Yates said. “But they never left.”

NPCA @ WORK

Some bats, it seems, spend winters in niches in the park’s rocky scree and talus slopes, hibernating alone or in small groups. Tim Divoll, a former Acadia researcher now doing bat work at Indiana State University’s Center for Bat Research, Outreach, and Conservation, said this behavior might actually help bats avoid infection. “If bats in Acadia are truly roosting by themselves in those slopes, it probably wouldn’t be a good place for the fungus to grow,” he said. While losses in the park have already been great, this could improve the chances of Acadia’s bat populations rebounding. Since the fungus is most destructive to large colonies in caves, bats that have adapted to wintering in tiny, “non-traditional” hibernacula may have a better shot at staying healthy, mating, and recovering their species.

Though he is focusing on the Indiana bat, one of the country’s most endangered Myotis species, Divoll sees mild signs of hope. The leap from detection of the fungus to major declines in summer populations took a full year longer in Indiana than in Acadia, for example, which may suggest the contagion is encountering resistance, either from bat antibodies or other environmental factors like weather patterns or topography. “Each year the disease’s footprint grows, but it seems to grow slower,” he said. He notes that in warmer climates, afflicted bats appear to have lower mortality rates. Despite the odds, some bats are actually surviving, he said.

Some conservationists are developing new tools for fighting, or even curing, white-nose syndrome. For several years, researchers at Georgia State University have worked with the U.S. Forest Service to develop a treatment for WNS. Common soil-dwelling bacteria found to delay ripening of bananas were turned on the fungus, with promising results. In May 2015, successfully treated bats were released into the wild in Kentucky and Missouri. Encouraging research is also under way at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where scientists have isolated antifungal bacteria found naturally on the skin of bats and applied them to sick bats in a concentrated spray. Though not ready for large-scale deployment in caves, these tactics eventually may allow more infected bats to survive winters and fight off the fungus on their own, as their body temperatures rise.

DeeAnn Reeder, a biology professor at Bucknell University who is at the forefront of WNS research, believes the key to cracking the disease may lie in genes of bats that have survived. “The remnant populations appear to be stabilizing,” she said. “It’s possible they were the lucky ones, but I don’t think that’s the case. They’ve likely seen exposure to WNS, but have survived and are persisting. So what makes them special?” Her team has theorized that these bats may respond less aggressively to infection, helping them conserve winter energy. “We suspect the surviving bats have behavioral and physiological differences in how they deal with hibernation,” she said. But even as understanding of WNS deepens, Reeder emphasizes responsible damage control over trying to conquer nature. “You can’t eliminate a pathogen like WNS. The goal is to manage and mitigate the disease.”

When it comes to Acadia’s bats, Connery is cautiously optimistic. “I think we’ve made good strides,” he said. “In general, we’ve been able to take some preventive, precautionary steps that are giving the bats a chance.” One such step has been postponing cutting or forestry projects in bat-rich areas during the summer months. Protecting the park’s bats is especially critical now, he said, because he’s also seen evidence that populations could be stabilizing: While mist-net yields in summer 2015 were still pitifully low, virtually none of the captured bats showed scarring or other signs of the disease. “We’re seeing individuals without exposure to WNS. It’s encouraging,” he said. The remaining bats could be successfully avoiding the disease, or they could be genetically and behaviorally resistant to the fungus—as Reeder’s research may suggest—or both.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›In 2016, the biggest challenge will be to protect bats roosting in trees and park structures as maintenance crews ready Acadia for the 100th anniversary of both the park and the Park Service this summer. The centennial celebration could boost the park’s 2 million-plus annual visitors to even higher numbers, and Connery said striking a balance between accommodating crowds and bat conservation may prove tricky. Renovations on the park’s 50-year-old visitor center were delayed earlier this year, for instance, when bats were found roosting in the building’s cedar shingles. Meanwhile, as public awareness of white-nose syndrome grows, he and his staff hope more people will see bats for what they are: fascinating, highly evolved creatures that provide invaluable natural services and represent an apex of biodiversity. One in five mammals on the planet is a bat.

And the nocturnal world of bats also offers a strange beauty, according to Yates, who used to research songbirds and loons. “Bats are the birds of the night,” he said. “Just like when we wake up in the morning and the birds are singing and it’s loud and the forest is alive.” Each night, just beyond the range of our perception, a mysterious, ultrasonic chorus fills the sky. “They’re singing and they’re calling and they’re echolocating,” he said. “But we just can’t hear them.”

About the author

-

Dorian Fox Contributor

Dorian Fox ContributorDorian Fox is a writer and freelance editor whose essays and articles have appeared in various literary journals and other publications. He lives in Boston and teaches creative writing courses through GrubStreet and Pioneer Valley Writers' Workshop. Find more about his work at dorianfox.com.