Spring 2016

Then and Now

Out with unchecked looting and feeding the bears. In with prescribed fire and zero waste. What a difference 100 years has made for the National Park Service.

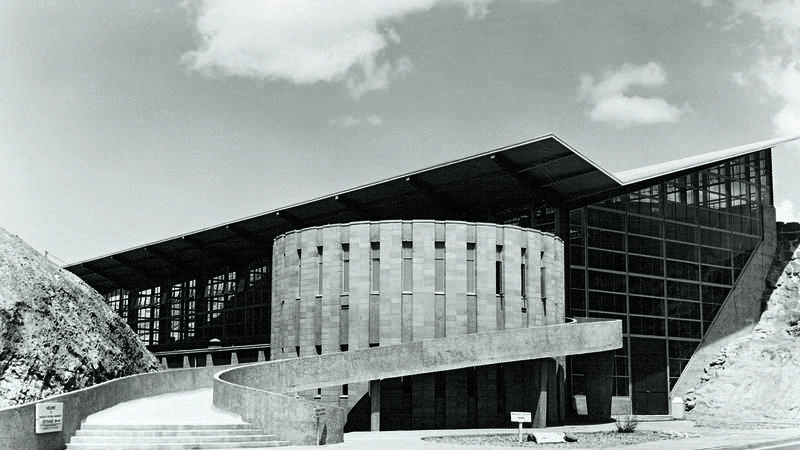

THE VISITOR CENTER GROWS UP

Quarry Visitor Center, a Mission 66 project at Dinosaur National Monument, was completed in 1958.

NPSTHEN: If you visited a national park in the late 19th or early 20th century, you wouldn’t have found a well-ordered visitor center; more likely, you would have trudged through a museum clogged with dusty artifacts and taxidermied animals. “The concept was more like what you would see at a natural history museum,” said Ray Todd, director of the Denver Service Center, the central design and construction office for the National Park Service. After World War II, visitors flocked to the parks and staff scrambled to keep up with their needs and questions. In response to the influx, in the mid-1950s, the Park Service initiated Mission 66, a decade-long, billion-dollar program that vastly improved buildings and gave birth to a shiny new idea: the visitor center. These new buildings offered visitors one-stop shops to get oriented, plan trips, buy supplies, and learn about the park’s resources. Gone was the modest, rustic architecture of the 1930s. Park sites such as Grand Canyon, Dinosaur, and Death Valley embraced a new mid-century modern design aesthetic that reflected the Park Service’s growing international reputation.

Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado opened its new visitor and research center in 2013.

ROBERT D. JENSEN/NPSNOW: In recent years, as Mission 66 visitor centers have been renovated or replaced, the Park Service has reassessed the need again. “There’s been a real focus on making visitor centers more sustainable and accessible—not only physically but programmatically,” Todd said. The newly renovated 16,000-square-foot White House visitor center, for example, has tactile exhibits for blind visitors and closed-captioned videos for the deaf. Exhibits feature efficient lighting, and bathroom facilities have low-flow fixtures. In addition, visitor centers are no longer plopped down right next to the main attractions. Now, architects site them more inconspicuously to blend in with the environment. “In all the work that we do, we try to be sensitive to the resources of the park and to embody our responsibility to be good stewards,” Todd said. “It becomes part of the story we tell.”

ART IN THE PARKS

THEN: In a letter published in the New York Daily Commercial Advertiser in the early 1830s, artist George Catlin advocated for “a nation’s park, containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty,” effectively becoming the first person to coin the national park idea. Other artists followed in his footsteps, many instinctively understanding that to be loved and protected, natural wonders had to be known. In the 19th century, the grand landscape paintings of artists such as Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran helped popularize Western wonders, and in the 20th century, photographs by Ansel Adams and others helped people see these wild landscapes as uniquely American attractions that rivaled the treasures of Europe.

NOW: Between 50 and 60 national park sites welcome artists-in-residence every year, from painters and sculptors to videographers and textile artists. And around the country, park employees host a range of art programs, organizing exhibitions or bringing in students and community members to participate in art projects. “We don’t think of it instantly, but art is a way of recreating and using the resource,” said Linda Cook, superintendent at Weir Farm National Historic Site, the only national park devoted to American painting. “There’s no question that being in nature and large open spaces is inspiring for the artist in all of us. That’s a fundamental human response.”

POACHERS, VANDALS, THIEVES, AND HOOLIGANS

U.S Army officers in Yellowstone around 1894 posing with buffalo heads taken from a poacher.

YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK/NPSTHEN: When Yellowstone was founded, in 1872, Congress didn’t appropriate funds to pay the superintendent, protect the resources, or develop tourist lodging. The result was a free-for-all. For more than five years, visitors shot elk and deer and fished the streams to oblivion. Captain William Ludlow, the leader of an 1875 scientific expedition to Yellowstone, wrote that people were “prowling about with shovel and ax, chopping and hacking and prying up great pieces of the most ornamental work they could find.” In 1883, after a series of Yellowstone superintendents failed to stop the chaos, the secretary of the Interior requested that the military take over. They succeeded in slowing the poaching and vandalism in Yellowstone as well as Yosemite and Sequoia.

A park police officer standing guard after a vandal splattered green paint on the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall in 2013.

© J. SCOTT APPLEWHITE/AP PHOTONOW: Today, cases of poaching and vandalism are much rarer, but they still exist in different forms. Poachers filch ferns and mushrooms from parks in the Pacific Northwest, old and rare cacti from the Southwest, ginseng plants in the mountainous Southeast, and burls from redwood trees in California. And vandals frequently deface historic structures and objects, such as Civil War cannons. Fortunately, the Park Service now has a nationwide law-enforcement arm to combat such problems, and the worst crimes make headlines. Last fall, the host of a hunting show, The Syndicate, and several other hunters were charged with poaching dozens of big-game animals, including grizzlies, caribou, and Dall sheep, in Noatak National Preserve. In 2014, a self-described artist defaced rocks at Crater Lake, Death Valley, Zion, and Canyonlands and was quickly caught after she posted her “artwork” online. “One of the elements of social media is people feel much more free—and sometimes that’s not to their benefit,” said Charles Cuvelier, chief of law enforcement, security, and emergency services for the Park Service. “I don’t think people appreciate the fact that public display of their actions can get them in trouble.”

GOING UP IN FLAMES

THEN: In August 1910, a dry summer and vicious winds fueled wildfires that burned 3 million acres of forest in Washington, Idaho, and Montana. The fire burned so hot it created tornado-like winds, pulling trees up from their roots and turning them into exploding firecrackers. Whole communities were incinerated, 86 people perished, and soot darkened the skies as far as New York. “It would have been just terrifying to be in that situation,” said Tina Boehle, fire communication and education specialist for the Park Service Division of Fire and Aviation, “and it lived on in the psyche of Westerners.” The nascent Forest Service, largely founded to facilitate logging, adopted a policy of fire suppression—“it was put it out fast, put it out small so it couldn’t get large,” said Boehle, and the Park Service followed that lead. But even as early as the 1920s, some leaders in the agency started to question the policy. In Sequoia National Park, the understory grew so thick it obscured the great trees, and one superintendent even experimented with prescribed fire, flouting the guidelines. Meanwhile, scientists were discovering that fire is a critical element in ecosystem health. Ultimately, the policy changed and park administrators were permitted to manage fires in a more nuanced way, even allowing them to burn when appropriate. In 1958, the first approved prescribed fire burned in Everglades National Park.

A firefighter monitors a back-burning operation intended to help contain the so-called Rough Fire of 2015, which burned more than 150,000 acres in and around Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.

© MAX WHITTAKERNOW: Even though federal agencies changed their fire management policies, decades of suppression dramatically altered the composition of the nation’s forests. “You can see a direct correlation with past fire suppression and current conditions,” said Tom Ribe, author of Inferno by Committee: A History of the Cerro Grande (Los Alamos) Fire, America’s Worst Prescribed Fire Disaster. Many forests are overgrown with small trees, making it easier for them to ignite and to burn hotter and longer when they do. As the climate shifts and Western droughts persist, the challenge of wildfire has intensified, but modern firefighters have advantages their predecessors couldn’t have imagined. Though they still use shovels, axes, and Pulaskis, they have a range of additional tools including mapping applications, satellite technology, helicopters, and, more recently, drones with infrared technology, which can scout an understory fire, augmenting efforts on the ground. In addition, the use of prescribed fire has grown dramatically: Over the last decade, 155 park sites have completed at least one controlled burn.

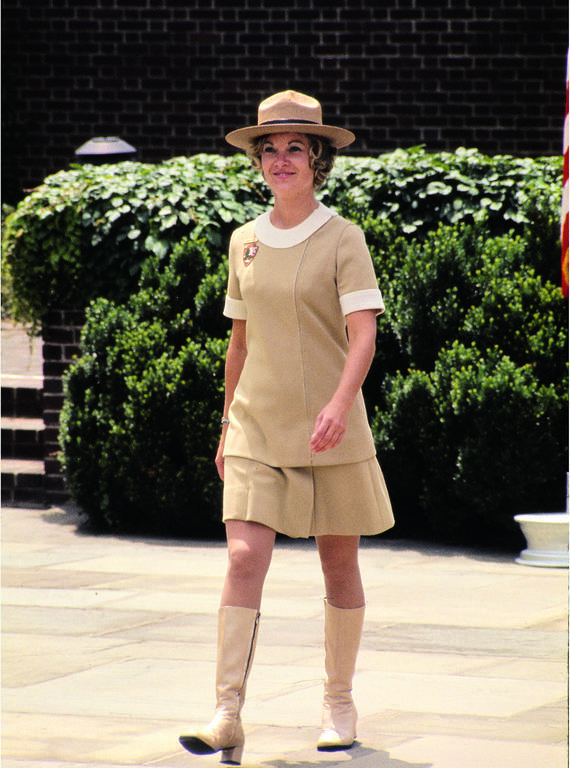

CHANGING FACES

A women’s Park Service uniform, unveiled in 1970, featured culottes, a tunic, and go-go boots.

CECIL W. STOUGHTON/NPS HPCTHEN: The Park Service has always been a product of its time, reflecting the mores—and prejudices—of the country it serves. In the early days, being a ranger was considered a man’s job, and park staff were largely white men with only a few exceptions. In 1918, “Rangerette” Helene Wilson checked in cars at Mount Rainier National Park, and Clare Marie Hodges acted as a ranger in Yosemite (though that title was reserved for men). In the 1960s, more women trained to be rangers, but they were still discouraged from fighting fire, enforcing the law, and discussing topics such as war. It wasn’t until 1978 that female Park Service employees were allowed to ditch their stewardess-like skirted uniforms—complete with go-go boots—and to wear the traditional ranger uniform, badge, and iconic hat. Non-white employees and visitors faced their own set of challenges: Buffalo soldiers acted as some of the first park rangers in Sequoia and Yosemite but otherwise, very few African Americans joined Park Service ranks in the agency’s early days. Some Native American groups were displaced when lands were settled and later turned into parks, and in Yellowstone, they were even treated like props to be photographed for the entertainment of visitors. In the Southeast, during the Jim Crow era, many parks maintained segregated campgrounds and picnic areas. “Who was the Park Service created for?” asked Sangita Chari, program manager for the Park Service’s Office of Relevancy, Diversity and Inclusion. “It was really the post-war generation of white, middle-class families looking for a place to vacation. That was who felt welcome, who was targeted, and who came.”

FIVE THINGS THAT NO LONGER HAPPEN IN THE PARKS

NOW: For years, many within the Park Service have strived to include more women and minorities, but the effort has accelerated recently with agency-wide efforts to hire and retain minorities, tell the stories of a much wider range of Americans, and welcome visitors who better reflect the changing demographics of the country. In 2013, the Park Service established the Office of Relevancy, Diversity, and Inclusion to help shape these efforts, which include developing recruitment strategies, offering webinars, and founding resource groups for Native Americans, African Americans, Latinos, and LGBTQ employees. Women now make up about 37 percent of the Park Service workforce, but minority representation in both employment and visitorship still lags. “Society around us is talking about these issues like we’ve never talked about them before, and I think it’s influencing the Park Service,” Chari said. “This is all just getting a place in the organization, and it’s making a difference. Our potential is so exciting.”

BEAUTY OF THE BEASTS

THEN: National parks were not established for the wildlife, but it didn’t take long for park leaders to realize that some animals could be crowd pleasers. Guided by a then-current ethos about “good” and “bad” animals, early park administrators engaged in some management practices that are surprising by today’s standards. In Yellowstone, for example, they fed hay and other food to popular species, killed predators, and poured non-native fish into streams for the delight of sport fishermen, a practice that persisted well into the 20th century. (To be fair, the U.S. Cavalry, which administered Yellowstone before the Park Service, also worked to protect animals and is credited with preventing the park’s bison from going extinct.) But over time, new Park Service leaders began questioning and changing earlier tactics, and an ethic of stewardship rooted in ecological thinking began to take hold. By the middle of the century, thanks to a groundswell of scientific study, the agency started managing wildlife with the intention of preserving “naturalness.” But what is natural? The question has inspired fiery—and productive—debate for decades and helped usher in a new era in conservation. This alternate outlook birthed important legislation including the Wilderness Act and the Endangered Species Act and has led to large-scale restoration efforts such as the reintroduction of bald eagles, peregrine falcons, wolves, grayling, and other imperiled species.

NOW: By the late 20th century, long-term studies had helped scientists understand that ecosystems are much more dynamic than previously thought. The widespread belief in the balance of nature started to give way to acceptance of the idea that ecosystems are always changing. The shift has spurred biologists and wildlife managers to conceive of conservation much more broadly. Now, in national parks, it’s not a matter of simply increasing or decreasing the number of animals such as elk in a given region but allowing the population to fluctuate naturally across both space and time. And in the face of climate change, it’s not a matter of conserving islands of natural areas, but whole landscapes that transcend political boundaries. “I believe that we have a responsibility to manage our lands closely with a wide range of partners to provide the time and spatial scales necessary for wildlife to continue to evolve,” said Glenn Plumb, chief wildlife biologist for the Park Service. “And as long as we can do that, then we will preserve them into the future, unimpaired.”

TRASH TALK

A vintage postcard of bears eating from a garbage wagon in Yellowstone.

NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

THEN: In the early days of the national parks, visitors may not have had disposable plastic, but they had plenty to throw away. And all that refuse went straight into dumps conveniently located not far from the main attractions. In some places, such as Yosemite, the dumps proved to be attractions in themselves as bears came to feast. Rangers even set up artificial feeding areas and bleachers so visitors could get a better view. By the 1940s, biologists realized the practice was bad for bears—and humans—and discontinued it. In Yosemite Valley, staff are still working to clean up historic trash dumps.

NOW: Many remote national parks still struggle with what to do with trash. In Yosemite, for example, 1,400 tons of trash are trucked out of the park to nearby Mariposa every year. It’s a laborious practice, but it could be worse: Staff and the park concessionaire have made extraordinary strides in reducing waste. In 1975, they started recycling across the park and now recycle more than 30 materials. In 2011, they installed water-refilling stations to cut down on single-use plastic water bottles. More than 90 percent of the dishes at dining facilities are compostable, and they currently collect 6,000 gallons of vegetable oil waste annually to be reused as biodiesel. And this year, Yosemite, along with Denali and Grand Teton, teamed up with Subaru and NPCA on a program to drastically reduce their refuse using zero-waste practices developed by the automaker.

FORWARD TO THE PAST

THEN: There was a time when the Park Service’s version of American history focused almost entirely on what famous white men did. In recent years, however, as methods in the field have evolved, historians at the agency have endeavored not only to tell the stories of previously overlooked groups but to move beyond dates and dry facts to include narratives and individual perspectives. Civil War battlefields are a prime example. In 1933, the Park Service inherited the battlefields and set up visitor centers that cataloged the movements of the armies. But those military details didn’t tell a complete story or place the war in a greater historical context. “We felt like we were missing a lot by not talking about why they were fighting in the first place,” said Robert Sutton, the former chief historian for the Park Service. “And it was important to broaden the story to be more holistic and hopefully provide more of interest to a wider audience.”

NOW: Many Civil War battlefields, such as Gettysburg National Military Park, have developed much more nuanced exhibitions and programs. Gettysburg’s new visitor center, which opened in 2008, better explains slavery as a major cause of the war and includes not only the relevant military movements but the perspectives of the common soldier, civilians, and farmers. “If you came in 2007, you came into this building and it was just a room full of stuff—guns by the hundreds, swords, rifles, bayonets, the detritus of battle,” said Christopher Gwinn, supervisory park ranger in interpretation and education. “The new museum is designed to tell you a story, so when you walk into the galleries, you’re walking through the American Civil War.” Visitors can still climb Little Round Top and visit Soldiers’ National Cemetery, but they can also learn about what happened after the battle, the cleanup effort, and how we remember veterans today.

GETTING THERE IS HALF THE BATTLE

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›THEN: In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, just getting to a national park was an adventure that required braving brain-jostling, multi-day train rides into undeveloped expanses of the country. To get to Acadia, the Northeast’s first national park, visitors traveled up the Maine Coast on a railroad, took a spur to Hancock Point, ferried across Frenchman Bay to Bar Harbor, and finally boarded carriages. From the beginning, visitor access was a primary concern for park proponents. They knew that for protected lands to thrive, they must have champions. Great road-building and trail-building efforts took place in many parks, resulting in robust networks that visitors still use today.

NOW: In the 1950s, the rise of the automobile allowed average middle-class families to access the parks for the first time, and they visited in unprecedented numbers. Now, so many cars pour into some parks, such as Zion and Yosemite, that buses shuttle people around to cut down on traffic. Meanwhile, other ways of accessing the parks have evolved. In Acadia, old carriage roads that John D. Rockefeller established starting in 1913 fell into disuse after his death, but they were rehabilitated in the 1990s and now are popular with horseback riders, cyclists, walkers, and joggers.

About the author

-

Kate Siber Contributor

Kate Siber ContributorKate Siber, a freelance writer and correspondent for Outside magazine, is based in Durango, Colorado. Her writing has appeared in National Geographic Traveler and The New York Times. She is also the author of “National Parks of the U.S.A.,” a best-selling children’s book.