Winter 2012

Something in the Water

Meet a few of the people who are joining forces to secure the region’s lifeblood, and ensure New River Gorge National River’s future for the next generation.

Every year, the New River Gorge National River in West Virginia draws more than 1 million visitors to experience its exhilarating white-water rapids, top-tier rock climbing, and abundant wildlife ranging from black bears to bald eagles. But the geography of the deep, tree-covered gorge that gave the park its name forced nearby cities and their antiquated wastewater systems to be built up on the plateau—upstream—of the powerful roiling river. This means that there’s no guarantee that the water flowing through the New River will be as crystal clear as you might expect. Ensuring clean water in this river park requires the concerted efforts of those who live and work in the surrounding communities.

It’s not something that most people like to think about when they’re swimming in the New River Gorge or paddling its world-class white water. But the reality is, this isn’t a waterpark or a Disneyland ride with freakishly blue, super-chlorinated water. More than 90,000 people live near streams that drain into the New River Gorge National River. If clean water is to flow through its length, then that clean water must come from the more than 15 sizeable creeks that flow into it. And that requires the efforts of all local residents and the work of hundreds of people who maintain sewage pipes and storm-water systems, who monitor water quality, who design and implement restoration projects, and who educate the next generation of leaders. Without clean water, there are no tourists, there are no bald eagles, no smallmouth bass and no rainbow trout, there are no beautiful photos, there are no whitewater rafting companies, no rock-climbers, and no quaint bed-and-breakfasts. The members and supporters of the New River Clean Water Alliance are fighting to preserve the elements of the place they call home. Although it may not be glamorous work, it’s crucial to the health of this national park unit.

Don Striker

Superintendent

New River Gorge National River

Glen Jean, West Virginia

Don Striker’s three children are nearly grown up now, but they still have memories of learning to ski in Yellowstone and learning to kayak on Oregon’s Columbia River. Now they enjoy all the New River has to offer as rock climbers and rappellers; the oldest two are even certified whitewater raft guides. Striker was closely involved in efforts that led the Boy Scouts of America to select the region for their fourth national high adventure camp and permanent jamboree site, and he sees the importance of reaching out to the region’s next generation of leaders.

As a park superintendent, there is no more important goal than to make sure you are relevant to your neighbors. If you’re not relevant to your neighbors, you have a long row to hoe. This work is all about community relations—this park isn’t an island. We can’t close a gate and hope to exist without the 18 different communities that surround us. And that’s why paying attention to local economic conditions is important. It’s also why it’s so important to pay attention to kids and their education.

This region has an unbelievable amount of poverty, so even though it’s a rural community, children here have just as few advantages as many of the urban city kids, so I wanted to connect our specific disadvantaged population to the amazing things this park has to offer. My goal is simple: I want every child in southern West Virginia to be a steward of their public lands by the time they graduate.

The Rangers in Training program asks: How can I connect kids in my local area to the park in a way that is relevant to them? These kids are out there rock climbing and rappelling, and they’re getting their environmental education on the side while they are doing cool things. Last year, my daughter and I paddled along a gentle stretch of the New, and saw a bald eagle with two or three of her young, nesting on Brooks Island, in the middle of the river. I want every kid in this area to experience a moment like that.

We try to increase capacity of these kids to recognize that they do have an ownership stake in their public lands and therefore responsibility, and also to attract them to jobs in the public lands and the Park Service specifically, if they show an interest.

Clean water and clean air are not just important to our health and our children’s health—they’re driving our recreation industry. We have a huge job in front of us. It’s neat to watch things evolve. I’ve been here four years and even in that brief amount of time, we’ve seen dramatic, measurable changes. People here are hungry for this sort of thing.

Jennifer DuPree Liddle

Southern Basin Coordinator

West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection

Oak Hill, West Virginia

One element of Jennifer DuPree Liddle’s job is helping small communities in and around the New River Gorge implement systems to keep human waste out of streams. It’s about as glamorous as it sounds, but it’s important work. And it’s changing the region. DuPree considers it her responsibility to put government funds to good use and to educate others about southern West Virginia’s lack of wastewater infrastructure—in plain English, that means a modernized system of pipes and treatment plants. Liddle loves the region because it offers something for every season: cross-country skiing in the winter, birding in the spring, paddle-boarding and other water sports in the summer, and camping anytime. And, of course, she loves the people.

Eight or nine years ago, my husband and I left the Florida Keys to come to West Virginia, where we essentially got paid to hike through the Gauley River National Recreation Area, including the Meadow River. We brought along a GPS unit to document rare plants that were important in the area. Our neighbor had a raft, and we rafted on day 1. It was an adventure. That season, we made at least 25 trips down the New River.

I feel like it’s my mission to let everyone know that in many ways our infrastructure in the coal fields is like that of a third-world country. When Bill Clinton came here to speak [at Fayetteville High School] in 2008, I shook his hand and let him know that 67 percent of the people in a nearby county lack adequate wastewater treatment—that means when they flush their toilet, it goes straight into a nearby stream. Even though there is more economic development near the New River, there are still communities with straight-pipes dumping waste right into the water, and some other difficult issues to deal with.

When the New River Clean Water Alliance had its first meeting, I really got excited that we had a big-picture approach. We all have different roles, but we share the same mission. People care about the New River. You cannot see fecal coliform bacteria, so until you have a significant problem you really don’t think about it. But there are enough people who use the resource that we can create partnerships and get results.

The rewarding part of this job is educating volunteers to monitor the streams in their own backyard, speak out, and feel comfortable talking about what’s in their water and what people can do to make things better at home. We’re not telling them what to do, just showing them how to do it.

Levi Rose

Wolf Creek Watershed Coordinator

Fayetteville, West Virginia

Levi Rose is a strong, soft-spoken 30-year-old environmental leader who was drawn to the area because of its world-class rock-climbing opportunities. Two years ago, Rose became the first watershed coordinator for Wolf Creek, teaming up with numerous agencies and local citizens for stream restoration, and putting his background in geology and biology to work for clean water. Much of his work focuses on finding ways to filter water that flows through abandoned mine lands, a problem created decades before environmental regulations made it illegal to leave mining waste behind. Levi’s position is made possible by a highly engaged group of concerned citizens who formed the Plateau Action Network 14 years ago.

In today’s economic climate, rather than look for a job, it is almost easier to make your own niche. For me, that’s been the greatest thing about coming here: recognizing a need, getting to know the right people, and having the opportunity to [make a special place even better]. I’ve gotten such great feedback from the community—people want clean water; that’s what’s keeping me here.

One of the great things about cleaning up Wolf Creek has been finding others that are just as passionate. For example, while working on the Summerlee Project, an adjoining landowner, Bill Fedukovich, won the construction bid and became an instrumental part of the project. Because he owns property here, he really wants to see the contaminated water cleaned up. Some days, Bill is more excited than I am—he’ll say ‘Check this out, this is working!’ There have been a lot of challenges with this project, but by combining our experience in this unique setting we have created something we’re both proud of.

In addition to securing grant funding to clean Wolf Creek, I have also partnered with Penn State University. The school was awarded a grant to study advances in purifying water polluted by mining waste, so their PhD and masters students have been coming down to help us collect water-quality data and study our efforts to remove iron from the system. And we’re already seeing some reductions. We predicted 40- to 60-percent reduction in iron for this particular system, and we’re already finding a 36-percent reduction, and we’re not even finished. When you can implement something and see that your desired outcomes can be achieved, that’s really rewarding.

Mary Lou Haley

Board President

Summers County Chamber of Commerce

Hinton, West Virginia

Mary Lou Haley’s office is a restored log cabin in Hinton, West Virginia, just upstream of the New River Gorge National River. A retiree who is deeply dedicated to the Hinton area, Haley wears many hats in the community, serving on the Summer’s County Chamber of Commerce, New River Community Partners, and the Hinton Area Foundation, to name just a few. Mary Lou Haley loves the river and has spent time along the New and Greenbrier Rivers her whole life. In 1991, Haley moved closer to the river, so she could experience it all the time. She still lives there today.

At the chamber of commerce, people call every day wanting to know where they can stay, what they can eat, what sights are in the area, and what we have to offer in terms of recreation. “How far are we are from this destination? Are there facilities on down the river? How far down the river? And, what’s down there?” (Most people don’t even realize that the New River flows north, which means “down” is really up.) “Is it fit for swimming? Is it fit for boating? Can we fish in the river? Are there places to rent boats?” All these questions. I kid and tell people that I’m the telephone directory for southern West Virginia.

For our health and the health of everybody who visits here, it’s so important that our water is clean. That’s a number-one priority; it truly is. If our river’s polluted, people don’t want to be in it. If it’s polluted, then we won’t see the fish and wildlife that are a draw for the area. All of our recreation depends on good clean water.

People who come here from other places can’t believe what it’s like here. And it truly is—it’s a special place.

**R.A. “Pete” Hobbs

Mayor

Ansted, West Virginia

**Pete Hobbs left Ansted, West Virginia, in 1961 after graduating from high school, but like many West Virginians, he made frequent trips home to the mountains in the years that followed. In 1995, he returned to Ansted to complete the last 11 years of a 37-year career with AT&T, an opportunity that allowed him to telecommute. It was a decision driven by family connections, the vast beauty of the mountains, and a quality of life he hadn’t seen anywhere else in his extensive travels. In 2003, he became mayor of Ansted, and now he’s leading a push to invite more workers to the region’s amenities, in an age when millions of employees are no longer tied to an office building. Hobbs is also balancing the community’s history of relying on industries like mining and logging with a future that’s likely to generate more income from tourism and home-based internet enterprise. And it all requires one thing: clean water.

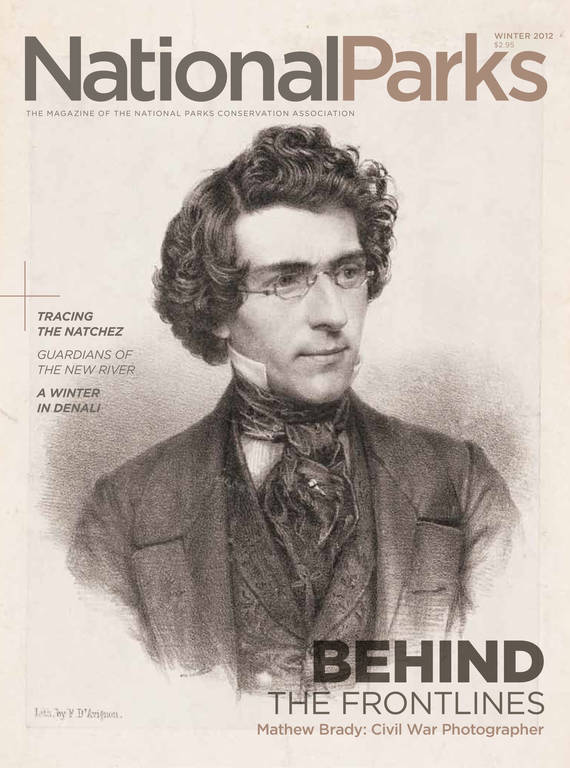

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›When I was growing up, I don’t think I would have found a botanist in residence in Oak Hill or Fayetteville. I don’t think I would have found a geologist here other than those interested in extracting coal. The introduction of a national park to an area, like the New River in 1978, brings a new level of highly educated workers.

And now, the beautiful underpinning of national park resources and state park resources will become key to the attraction of modern workers who want to work at home but demand a pristine living arrangement. They want more than just basic services—they want recreational opportunities, they want clean water, they want all of those things that are fundamental to a real high quality of life. We have all those pieces in place here and, of course, we still have our extraction industries around us that bring a great deal of revenue. We find ourselves in conflict from time to time because of either the perceived or actual damage to those elements of quality of life that are essential to move the tourism industry and recreational industries forward. The tourism-based element of our economic engine now is approaching the point where it is matching or exceeding the actual economic impact of the other traditional businesses that we have always relied on. Somehow, we here have to find those innovative ways to make all of that work together.

Federal dollars allocated to the parks can bring economic stability to an area as they have done here in central West Virginia. I will continue to advocate for the parks because I think the parks not only provide that economic balance to areas that are typically very remote, but they’re clearly worthy of preserving in their own right. It all tugs at a lot of emotional elements for me—these are the things that make me want to get out of bed every morning.

About the author

-

Heather Lukacs and Scott Kirkwood

Heather Lukacs and Scott KirkwoodHeather Lukacs is a program manager for NPCA’s West Virginia Field Office, and a founding member of the New River Clean Water Alliance; Lukacs has led white-water rafting excursions through the gorge since she was a high school senior. Scott Kirkwood was the editor in chief of National Parks magazine; his first white-water rafting trip was on the New River 20 years ago.