Winter 2012

Mathew Brady, the War Correspondent

If you’ve ever seen a portrait of a Civil War soldier or the landscape of a battlefield just after the cannon-fire has been silenced, then you’re familiar with the work of Mathew Brady. Now meet the man behind the images.

Cannonballs obliterated trees, bullets and mortar shells whizzed every which way, and bodies fell again and again. In the midst of all the smoke and carnage, at the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861 stood (and, presumably, ran) the distinguished photographer Mathew B. Brady. Out to capture scenes from the Civil War’s first major clash, Brady and his assistants found themselves in tumultuous and nerve-racking circumstances as the formerly dominant Union forces they’d set out to celebrate in pictures were pushed back toward Washington, D.C. Brady and company followed. And even though some claimed or implied otherwise, no images of that day survived. Brady, fortunately, did, and thereafter his cameras recorded history in the making.

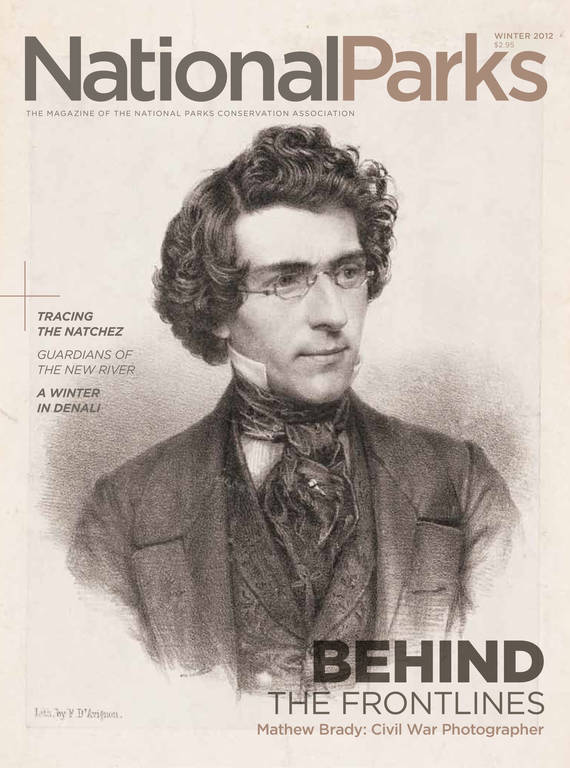

Although Mathew Brady is strongly associated with the hundreds of Civil War photos that bear his name, the man was actually quite famous before the first cannon was fired. A couple of stair flights above the eternal bustle of Broadway in 1850s New York was a sumptuous oasis filled with famous faces: business tycoons, powerful politicians, military men, and beloved entertainers. Many of them stared back, motionless, from between rosewood and gilt frames that lined and leaned up against nearly every satin-and-gold-papered wall. A number of more animated visages belonged to visitors, notable and not, who milled about on velvet tapestry carpets beneath a frescoed ceiling from which hung ornate chandeliers. Lots of these visitors—including decked-out denizens of the middle class—came to see and be seen and, very often, to have their own likenesses captured by the establishment’s oddly bearded and bespectacled owner. “Brady of Broadway,” as he was popularly known, would soon migrate farther north to even more expansive and luxurious digs (dubbed the “National Portrait Gallery”). He’d also open a successful branch office in Washington, D.C.

One of the country’s most sought-after photographers, Brady was by now something of a celebrity himself. Having established his first gallery on a less fashionable strip of Broadway in 1844, the Warren County, New York-born entrepreneur had quickly ingratiated himself with the era’s movers and shakers. “Mr. Brady has the happy faculty of being attentive without being officious, of possessing suavity without obtrusiveness, and is altogether the right man for the right place,” declared a typically flattering story from the 1850s in Frank Leslie’s Weekly. But it was more than Brady’s solicitous manner that lured patrons in droves. Wrote Mary Panzer, author of the book Mathew Brady and the Image of History, “His portraits revealed his sitters to themselves, and to the world, as they most wanted to appear.”

Brady often charged no fee to stars of a certain stature to impress other prospective patrons. Schooled in part by Samuel F. B. Morse, an artist and future inventor of the telegraph, Brady first made his mark as a “daguerreotypist.” Tedious and time-consuming, the daguerreotype process went thusly: silver-plated copper sheets were bathed in nitric acid and exposed in a darkroom to iodine vapor before being inserted into a boxy wooden camera on a tripod and introduced to light. Afterward, when warm mercury vapors hit the silver, images appeared. Subjects sat or stood statue-still, frequently while secured in place with an iron head clamp, for up to one minute (a vast improvement from the early days, though still long enough to elicit the mirthless expressions so common to photographic subjects of that era). Before long, a more efficient technique called “wet-plate collodion” photography yielded enlargeable albumen silver prints that could be reproduced in limitless quantities. Brady swiftly mastered that method as well.

And though it would spark critical debate decades later, no one thought twice of the fact that Brady not only appropriated—sans permission—the work of others and slapped his moniker on it but took virtually none of his own shots. (The U.S. Congress didn’t establish copyright laws until 1865.) Employees did much of the work, with Brady serving as a sort of artistic director and executive producer. “The person who was manipulating the camera was really just seen as a technician,” says Ann Shumard, curator of photographs at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. “What made it a Brady was the fact that he was there to pose the subject and to really set up the shot. It didn’t matter who was behind the camera or who was in the back room developing the plate. There was a Brady look and a Brady standard and he set that through his own artistic vision.”

In late February of 1860, a lanky and beardless lawyer and legislator from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln dropped by Brady’s latest New York establishment at 10th and Broadway while in town to give a speech at Cooper Union. He’d return thereafter for another sitting, bearded and considerably more burdened. And when the 19-year-old Prince of Wales made a tour of the States that same year, a portrait session at Brady’s reportedly topped his list of priorities. In March of 1861, Brady set up shop at the Capitol building in Washington, D.C., to record Lincoln’s inauguration. After the Great Emancipator died from an assassin’s bullet, just as the Civil War was winding down in mid-April of 1865, Brady’s cameras were present at his crowded funeral procession in New York.

In the four years leading up to that moment, Brady’s portrait-centric work took a back seat to something he suddenly considered far more important. The country was deeply divided, Southern states had begun seceding from the Union, and by July of 1861 Bull Run signaled the start in earnest of a vicious and protracted civil war. Thus began the most significant phase of Brady’s career. Snapping presidents and judges, congressmen and industry magnates was fulfilling to an extent, but the war offered Brady an opportunity to document history as no one else had—as, in effect, the progenitor of photojournalists. Of course, he hoped doing so would also enhance his already stellar reputation and fill his coffers. It was just a matter of how to proceed. Aside from some previous fieldwork done by such respected photographers as Roger Fenton during the Crimean War in Russia, few had transplanted the period’s unwieldy gear from a controlled studio environment to an unpredictable and often-hostile outdoor one with successful results. And there was no guidebook from which to glean advice. Brady, however, felt compelled. “My wife and my most conservative friends had looked unfavorably upon this departure from commercial business to pictorial war correspondence,” he told the New York World. “And I can only describe the destiny that overruled me by saying that, like Euphorion, I felt that I had to go. A spirit in my feet said ‘Go’ and I went.”

Still, as The American Scholar editor Robert Wilson recently noted in an article for The Atlantic, Brady—a dandified fellow who swaddled himself in the finest frocks and wore expensive cologne—was infinitely more comfortable out of the fray than in it. “At the very beginning of the war Brady went out there on the field of battle and it ended very badly,” says Wilson, who is working on a Brady biography. “My suspicion is that he was badly spooked.” Bull Run, as Wilson writes in his Atlantic piece, marked the first and last time Brady would put himself “in harm’s way.”

Throughout the war, acting like a small newspaper operation, Brady dispatched more than 20 staffers to various key locations, including battlefields—but only after fighting had ceased. The federal government, too, employed hundreds of photographers for, among other things, mapmaking and reconnaissance purposes, but Brady functioned independently and as a for-profit entity. “Certainly he was not the best, nor the most prolific, nor the most important,” Dorothy Meserve Kunhardt and Philip B. Kunhardt, Jr. wrote in their book, Mathew Brady and His World. “Nevertheless, he was by far the most famous.” Scotsman Alexander Gardner, a skilled craftsman in the wet-plate tradition who’d been on Brady’s payroll since 1856 and ran Brady’s D.C. studio for a few years, was one of his boss’s top technicians. Timothy O’Sullivan was another. But neither man received individual credit for his work. None of Brady’s bunch did. The only name that appeared on Brady-bankrolled photos was Brady’s, which caused no small amount of grumbling. Shortly after the Civil War commenced, in fact, Gardner quit Brady’s employ and earned acclaim on his own. Differences in what could be termed creative vision were common as well. Whereas charges like Gardner and O’Sullivan recorded images of the newly dead, Brady’s approach was softer.

When in Washington he sometimes ventured out to nearby battlefields with his double-lensed “stereo” camera and his horse-drawn darkroom (one of several retrofitted delivery wagons in his fleet). Because burial parties were in the midst of doing, or had already done, their grim duty, he moved about and set up shots with an ease that was unthinkable at Bull Run. On occasion, as he did following the battle of Gettysburg, Brady appeared (distantly and never facing the camera) in his own photos. And while concern for his own safety almost surely played a role in the timing of his field excursions, the circumstances under which Brady and his men toiled even post-battle were often less than idyllic. Weather was ever changing and temperatures ran the gamut from blazing hot to freezing cold. Flies and dust stuck to negatives. Clean water was in short supply. Corpses of men and horses lay bloated and festering in the searing sun, the odor of death almost overwhelming. “It was a very, very foul place to work, but yet they did it,” says Todd Harrington, a professional photographer and modern-day practitioner of the wet-plate collodion process used by Brady. “They knew what they were capturing was so revolutionary and so earth shattering because no one had ever done it.”

In September of 1862 the battle of Antietam marked a photographic shift. Instead of merely showing soldiers in their encampments or torn-up fields where blood had been spilled days or weeks prior, some of Brady’s charges began to reveal a darker version of events in the form of twisted corpses. (Because shooting battles in progress would have resulted in profoundly blurred images, such action scenarios were avoided.) The public reacted to these depictions with a mix of horror and intrigue. As The New York Times put it, Brady and his team did “something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.” The writer went on: “You will see hushed, reverend (sic) groups standing around these weird copies of carnage, bending down to look in the pale faces of the dead, chained by the strange spell that dwells in dead men’s eyes.” Harper’s Weekly, which filled its pages with engravings of Brady’s photos (another effective Brady publicity tactic) and was among his most ardent champions, lauded an especially poetic view of a bridge and creek at Antietam as “one of the most beautiful and perfect photograph landscapes that we have seen.” The same publication avowed that “if any man deserves credit for accumulating material for history, that man is M.B. Brady.”

But for all the time invested and money spent—by his own estimate, around $100,000—Brady’s Civil War foray proved financially ruinous. With some goading, the U.S. government eventually agreed to purchase thousands of negatives for $25,000. It was enough to pay down the by-then bankrupt Brady’s debts, at a fraction of his massive collection’s assessed worth of $150,000. Historically precious though his images were, they were also too-potent reminders of an event most people wanted to forget.

Although Brady continued to photograph dignitaries of the day for decades after the war’s end in a succession of studios, his enthusiasm flagged along with his popularity, his perpetually poor eyesight, and his overall health. Toward the end of his life, widowed and increasingly marginalized, Brady drank too much and embellished tales of his exploits and encounters. Civil War anniversaries briefly brought him a sliver of spotlight, but soon he receded back into shadows. On January 15, 1896, less than a year after being struck by a carriage that shattered a leg, Brady died in the indigent ward of New York’s Presbyterian Hospital. An obituary in The New York Times reported “Bright’s disease” (a kidney affliction) was listed in hospital records as the cause, “but his death was really due to the misfortunes which have befallen him in recent years.” He was 72. In that same obit, the Times thrice misspelled Brady’s first name—further evidence, perhaps, of the pioneering photographer’s diminished profile. Brady’s attempts to reverse his fortunes—to sell more of his war images, to burnish his legacy—had had little effect. “No one will ever know what I went through to secure those negatives,” Brady supposedly said of his prized war photographs. “The world can never appreciate it. It changed the whole course of my life.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›As would become apparent after Brady’s death, it also changed his medium forever, and for the better. “I don’t think there’s any question that Brady is the most important figure in 19th-century American photography,” says Wilson. “He helped establish it as a business and encouraged other people to go into the business.” Shannon Perich, associate curator of the Photographic History Collection at the National Museum of American History, notes that Brady was also among the first in his fledgling profession to establish himself as a formidable “brand,” along the lines of modern photo factories like Olan Mills.

When it comes to our understanding of the Civil War, experts say, Brady’s contributions to the historical record—the stark realism of those people and places immortalized by his deftly aimed lenses—are legion. Eloquently addressing that point in a 1946 review for The New York Times, the late American historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. asserted that Brady’s war scenes were “even more important” than his portraits in that they revealed “the resources of photography. The eye of Brady’s camera, serene, comprehensive, pitiless, caught for all time the sweep of the war, the violence and destruction, the terrible quiet and the terrible beauty.”