Summer 2011

Home of the Brave

Boston’s national parks lead visitors back in time to our nation’s beginnings.

On a recent excursion to visit the Freedom Trail, a 2.5-mile walking trail that wends among 16 historic sites in downtown Boston, I entered the Granary Burying Ground, final resting place of Samuel Adams and Paul Revere, among other Revolutionary Era Who’s Whos. Here, a teenage girl peered at a gravestone and whispered to her friend, “Didn’t we learn about him in U.S. History?”

Yes, I wanted to say, you probably did. Anyone involved in our nation’s founding probably crossed paths with this city at some time or another.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

Presidents were born here. Revolutionaries battled here. The idea of Liberty with a capital “L” simmered in these streets. But less-than-heroic events also smoldered here: In response to desegregation and busing, riots erupted, and off these shores, our government interred Native Americans and prisoners of war. For the peripatetic traveler, experiencing urban Boston is to experience a historical treasure hunt—even when the lessons contradict one another.

I live here, and I’m always astounded by how much history this city encompasses. I’m also a little embarrassed by what I ignore on my daily trips about town. Each time I’m anointed amateur tour guide, I’m reminded of the massacres, speeches, and tea parties that took place in the same cramped squares and streets now chock-a-block with chain restaurants and motorized vehicles. I’m also astounded by how much history I’ve forgotten—and how overwhelming it can be to try to catch up.

In a city where voices seem to whisper behind every crooked headstone that “So-and-So slept here,” it’s best to pace yourself. Fortunately, how you carve up your downtown Boston experience is up to you. Explore via guidebook, or for a richer experience, hop on a tour led by a ranger or civilian expert (role-playing the part of, say, Ben Franklin). All sites are walkable and accessible by public transportation, so leave your car behind and march into the 18th or 19th century—or even farther into the past, if you know where to look.

Boston National Historical Park

For newbies, a fine starting point is the Freedom Trail that winds through Boston National Historical Park. Unlike many properties in the Park Service, the Freedom Trail is neither a single site nor a swath of pristine land—it’s more of a march through time and place. Beginning at the gold dome of the Massachusetts State House on Boston Common, a red path zigzags along the sidewalk (sometimes marked in paint, sometimes in bricks), around parks, offices, and hotels linking burial grounds, museums, a ship, churches, and meeting houses. Historic markers along the way help tell the story of the American Revolution.

You’ll hit Granary Burying Ground first, where Adams, Revere, James Otis (who’s “taxation without representation” called colonists to arms), and other famous historical figures are interred; then King’s Chapel, the first Anglican Church in New England, which also features the first organ used in an American church and the oldest pulpit still in use in its original site. On special occasions, the church still rings the 1816 bell, “the sweetest bell we ever made,” according to Paul Revere, a silversmith and patriot best known for his ride from Boston to Lexington and Concord to warn of the arrival of British troops.

Not everyone in Boston during the Revolutionary Era was a revolutionary, however. Tories, loyal to the British Crown, also worshipped here, so the King’s Chapel offers a faint reminder of the British point of view, and the church continues to follow a form of the Anglican liturgy in its worship services today.

From the chapel, follow the red-brick road to the Old South Meeting House, where thousands of Bostonians plotted the Tea Party—a protest against a British tea tax that ignited the American Revolution. Nearby, the Old State House stands as the oldest public building in the nation, where the influential statesman Samuel Adams rallied others to resist British rule. Now, it’s a small museum and gift shop where tourists buy quill pens and baseballs emblazoned with the Declaration of Independence. (This is Red Sox Nation, after all.) Outside the museum’s door is the site of the Boston Massacre, a pivotal event in 1770 when England’s Redcoats killed five colonists, leading to brawls and kindling the war.

SIDE TRIP

The site that inspires me most is Faneuil Hall; if you’re lucky, you’ll hear park ranger Merrill Kohlhofer delve into the hall’s history while channeling the many voices heard there, including Frederick Douglass declaring, “I am a fugitive slave.”

After Faneuil Hall and nearby Quincy Market—locale for eateries, shops, and vending carts—the trail veers into the North End, home of a thriving Italian-American community, as well as the Paul Revere House and the Old North Church. (Yes, that church, the one immortalized by the “One if by land, two if by sea” secret code that Revere created to signal the British army’s route.) The trail then passes Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, the final resting place of Puritan ministers connected to the Salem witch trials, among other notable figures. Finally, the trail hops across the Charles River and through the lantern-lined streets of Charlestown to the Bunker Hill Monument and the Charlestown Navy Yard, where the USS Constitution, the world’s oldest commissioned warship still afloat, is moored. Many visitors end their urban hike at the Warren Tavern (2 Pleasant Street), founded in 1780, to rest their feet and enjoy a frosty beverage.

Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area

Not far from the Freedom Trail is Long Wharf, the launching point for the Boston Harbor Islands. Of the 34 islands, only seven are open to the public— Bumpkin, Georges, Grape, Little Brewster, Lovells, Spectacle, and Thompson—but you’ll still find a pirate’s booty of history as you zip from isle to isle by ferry (15- to 45-minute rides from Long Wharf).

Today, most of the islands are pristine, but in the past they served various unsavory purposes: prisoner-of-war camp, landfill, horse rendering factory, bordello, and small-pox quarantine, to name several. Now, the reclaimed spaces offer sunbathing, swimming, hiking, biking, bird watching, and rustic camping. Spectacle and Georges Islands have new interpretive centers and recreational areas and offer yoga lessons, jazz concerts, and children’s theater. Lighthouse buffs can climb Boston Light, the nation’s oldest continually used and human-run lighthouse on outlying Little Brewster Island. Sally Snowman, the only female lighthouse keeper in the country, works here, often in 18th-century dress.

The islands aren’t just for out-of-towners; they make an exquisite getaway for locals, too, who can take a subway train to the wharf, hop on a boat, and immerse themselves in island life within a couple of hours. On my last visit to the Harbor Islands, I camped on Bumpkin. The ferry dropped me at the dock, and I used a cart to wheel my gear to the campsite, then I joined new friends who were taking part in an annual artist-residency program. We grilled out, swam in the ocean, napped in the sun, and chatted by bonfire after nightfall—an epic park experience by any standards, and all within sight of the Boston skyline.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy National Historic Site

Just west of that skyline is the city of Brookline, a short trolley ride from downtown. Here, in a modest neighborhood, Joseph and Rose Kennedy purchased a house at 83 Beals Street shortly after their marriage in 1914. Three years later, on May 29 at 3 p.m., Rose Kennedy gave birth to their second son: John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States.

Although the house reflected a healthy economic status in Kennedy’s time, it’s hard to imagine how four adults (two parents plus two servants) and four children (Joe Jr., John, Rosemary, and Kathleen) managed to live here in comfort. “Rose was beginning to feel isolated, with the walls closing in around her,” says Jim Roberts, supervisory park ranger for the site. Nevertheless, this two-story home was the training ground for an ambitious couple with high hopes for their children’s future in public service: Rose hung reproductions of influential art on the walls and at dinnertime schooled her children in adult conversation and world affairs. In 1920 they moved across the neighborhood to a larger home at 131 Naples Road, and eventually relocated to New York City.

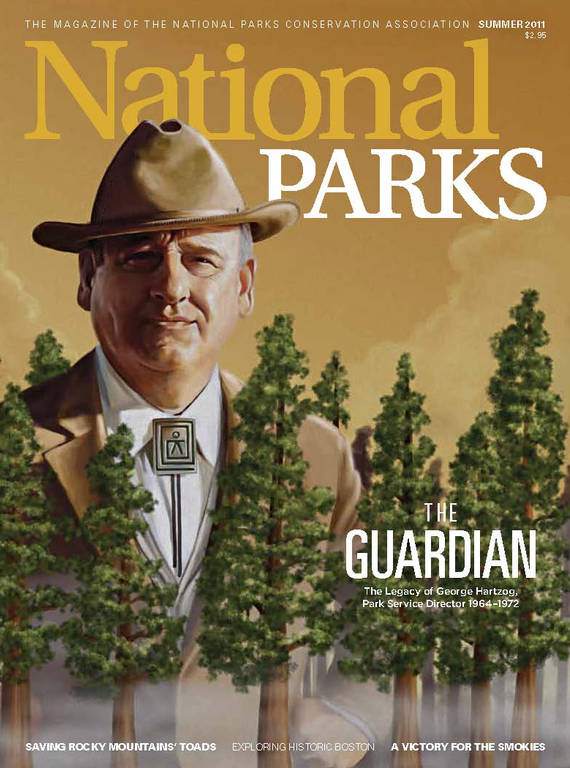

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Before handing the house off to the Park Service in 1969, Rose tried to recreate the day of JFK’s birth by decorating the home with period furniture and personal mementos such as family photos, the bassinet where many a Kennedy once dozed, and embroidered bedspreads from Ireland. Today, the dining room table is set with fine china and, next to it, on a smaller kids’ table, you’ll see a silver porridge bowl inscribed with the letters “JFK.”

“The Kennedys are the closest thing to American royalty,” Roberts says. “But they weren’t gods. They were people like us.” For scholars and citizens alike, there’s a good reason to visit in 2011, which marks 50 years since the beginning of the Kennedy Administration. “JFK is still in the minds of people all over the world,” says Roberts, alluding to the scholars, tourists, and historians who travel here to reconnect with this story.

Standing in the foyer, I was reminded that JFK’s legacy still resounds all over the city. I could suddenly feel the connection that runs like buried cable between this house and the many sites of the Freedom Trail, between the Revolutionary Era and the “Days of Camelot” (the JFK-inspired period of hope and optimism).

I was also reminded of something I learned from Kohlhofer on my tour of Faneuil Hall: JFK gave the final speech of his 1960 presidential campaign there. It’s the same place where, today, immigrants take their oaths of U.S. citizenship. “If you want to see anyone who is excited about becoming an American,” Kohlhofer said to the assembled crowd, “come here.” Come to Boston.

About the author

-

Ethan Gilsdorf Contributor

Ethan Gilsdorf ContributorEthan Gilsdorf, a Boston native, writes regularly for The New York Times and other publications worldwide.